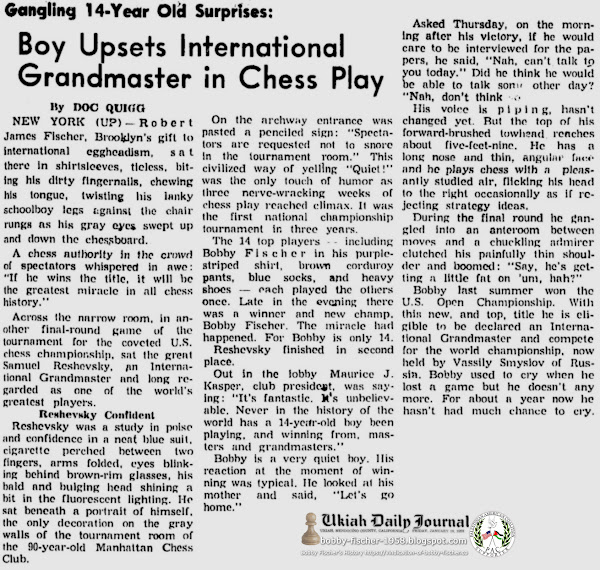

Ukiah Daily Journal, Ukiah, California, Friday, January 10, 1958

Gangling 14-Year Old Surprises: Boy Upsets International Grandmaster in Chess Play

By DOC QUIGG

New York (UP)—Robert James Fischer, Brooklyn's gift to international eggheadism, sat there in shirtsleeves, tieless, biting his dirty fingernails, chewing his tongue, twisting his lanky schoolboy legs against the chair rungs as his gray eyes swept up and down the chessboard.

A chess authority in the crowd of spectators whispered in awe: “If he wins the title, it will be the greatest miracle in all chess history.”

Across the narrow room, in another final-round game of the tournament for the coveted U.S. chess championship, sat the great Samuel Reshevsky, an International Grandmaster and long regarded as one of the world's greatest players.

Reshevsky Confident

Reshevsky was a study in poise and confidence in a neat blue suit, cigarette perched between two fingers, arms folded, eyes blinking behind brown-rim glasses, his bald and bulging head shining a bit in the fluorescent lighting. He sat beneath a portrait of himself, the only decoration on the gray walls of the tournament room of the 90-year-old Manhattan Chess Club.

On the archway entrance was pasted a penciled sign: “Spectators are requested not to snore in the tournament room.” This civilized way of yelling “Quiet!” was the only touch of humor as three nerve-wrecking weeks of chess play reached climax. It was the first national championship tournament in three years.

The 14 top players — including Bobby Fischer in his purple striped shirt, brown corduroy pants, blue socks, and heavy shoes — each played the others once. Late in the evening there was a winner and new champ, Bobby Fischer. The miracle had happened. For Bobby is only 14.

Reshevsky finished in second place.

Out in the lobby, Maurice J. Kasper, club president, was saying: “It's fantastic. It's unbelievable. Never in the history of the world has a 14-year-old boy been playing, and winning from, masters and grandmasters.”

Bobby is a very quiet boy. His reaction at the moment of winning was typical. He looked at his mother and said, “Let's go home.”

Asked Thursday, on the morning of his victory, if he would care to be interviewed for the papers, he said, “Nah, can't talk to you today.”. Did he think he would be able to talk some other day? “Nah, don't think so.”

His voice is piping, hasn't changed yet. But the top of his forward-brushed towhead reaches about five-feet-nine. He has a long nose and thin, angular face and he plays chess with a pleasantly studied air, flicking his head to the right occasionally as if rejecting strategy ideas.

During the final round he gangled into an anteroom between moves and a chuckling admirer clutched his painfully thin shoulder and boomed: “Say, he's getting a little fat on 'um, hah?”

Bobby last summer won the U.S. Open Championship. With this new, and top, title he is eligible to be declared an International Grandmaster and compete for the world championship, now held by Vassily Smyslov of Russia. Bobby used to cry when he lost a game but he doesn't any more. For about a year now he hasn't had much chance to cry.